Every story worth telling, and repeating has a beginning, a middle and an ending. Some great stories include foreshadowing, and almost story has a conflict that needs to be resolved. The ending aims to leave the readers with a sense of closure with the story having an ending that satisfying and wraps up all loose ends that came about in the body of the story. I am not an author, but I do hope to present the story of the Pulaski County Poor Farm in a sensible way that brings the stories of the people who lived, and died there to life. It is assumed that "inmates" as they were often referred to, most likely did not live with much dignity and respect during their lifetimes. It is my intention that piecing together and telling their stories, with my limited writing skills, will honor their memory and their history.

The quest for knowledge about Pulaski County Poor Farm's history began simply enough. During the summer of 2008, a visit to the 1903 Pulaski County Courthouse Museum, Laura Huffman saw an old ledger at the top of the staircase that leads to the upstairs courtroom. Beside the ledger was a typewritten piece of paper with basic information about the County Farm, as it was also known. The display also contained a photocopied article, written by Adlyn Shelden White, which was published in History Pulaski County Missouri Volume II, which was published in 1987. Another item in the display was an old typewritten, faded, yellowed sheet of paper, entitled "Suggestions as to Sanitation & Management of County Almshouses". And of course, the featured item, the old Pulaski County Poor Farm ledger.

The quest for knowledge about Pulaski County Poor Farm's history began simply enough. During the summer of 2008, a visit to the 1903 Pulaski County Courthouse Museum, Laura Huffman saw an old ledger at the top of the staircase that leads to the upstairs courtroom. Beside the ledger was a typewritten piece of paper with basic information about the County Farm, as it was also known. The display also contained a photocopied article, written by Adlyn Shelden White, which was published in History Pulaski County Missouri Volume II, which was published in 1987. Another item in the display was an old typewritten, faded, yellowed sheet of paper, entitled "Suggestions as to Sanitation & Management of County Almshouses". And of course, the featured item, the old Pulaski County Poor Farm ledger.

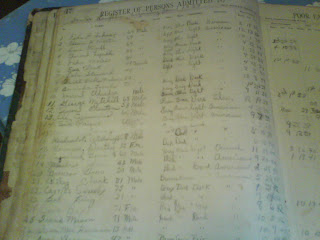

The Old Pulaski County Poor Farm Ledger. Photo by Laura Huffman, Summer 2009

The Old Pulaski County Poor Farm Ledger. Photo by Laura Huffman, Summer 2009The old ledger looked innocent enough, it was just lying there opened with two pages exposed for the visitors to see. Terrie Runion-Elmer and I admired the lettering in the ledger, commented on how handwriting styles had changed throughout the years, and then went about our business looking at the other exhibits that the museum has to offer.

Images of the old ledger took up residence in my mind and I just could not seem to shake it. I had previous experience with looking through old Masonic ledgers that had been in Grandpa Cletus Cato's possession. When my grandfather allowed me to read them I became engrossed in the entries and the glimpses in to the past that the entries provided. In the Masonic ledgers I was particularly struck by the penmanship of the man who recorded the entries. I could almost picture him dipping his quill in an inkwell as he made his marks in the journal. To my dismay, the handwriting changed, and as I feared the previous entry maker had indeed passed away. I kept on reading and my fears of his death were confirmed. This was not the end of the dated entries however, so I kept on reading. I learned that the widow of the deceased did not have enough money to pay for a headstone for her departed husband. I learned how the Masons had teamed together to raise funds to provide this gentleman with a tombstone that reflected his stature as a contributing person to the frontier settlement along the banks of the Castor River in Southeast Missouri. I read that a member of the Masons donated a horse to be sold at auction to raise funds for his stone. The entries in the Masonic ledger regarding the deceased described in great detail the stone that was purchased for him by his Masonic brothers. The description and detail of the headstone, including the Masonic emblem that was included on his marker led me straight to his grave site at Zalma City Cemetery in Zalma, Missouri. It was quite a feeling to be led directly to a spot by words that were written a hundred years before.

From the experience with the old Masonic journals, I knew that there were stories to be told in the old Poor Farm ledger as well. I returned to the 1903 Old Courthouse Museum during the summer of 2009 and explained to Museum Curator, Marge Scott, that I needed to look at the old ledger. I could see in her eyes that she was very concerned about letting someone, off the street, come in an handle a book that is approximately 135 years old, and the only copy in existence. I also think that she saw in my eyes that was something that I really felt that I had to do. Thankfully, and perhaps against her better judgement, but based on a gut a feeling, she allowed me to take the old ledger downstairs into the old vault room and start transcribing the names that were recorded in the old ledger. I was unable to transcribe all the entries my first day in the vault but as I was leaving, I promised to return the following Saturday and continue the work. As I walked out the museum that day, I am sure that Mrs. Scott had her doubts as to whether I would return. But return I did. For the next three Saturday mornings in August , I returned to the vault with the ledger, my notebook, a pen, and my cell phone camera until the basics of every entry had been recorded. Saturday, August 22, 2009 I returned to the Museum and presented a typewritten list, in chronological order and presented it to the Museum, Mrs. Scott, and Betty Atterberry. The list was by no means accurate. A lot of the entries were recorded in pencil that had faded through the years, and due to changes in writing styles sometimes I was unable to record the correct spelling of the names and had to haphazard a guess. Not the best research style, but being new at this, it was the best that I could do at the time.

This is one of the most touching stories I have read in my researching life. Part of the pain of genealogy to me is not knowing the details of the lives of those whose memory I love and those I would like to know. I have just started working on the Tippett and Tilley family history of Pulaski County and am so grateful to all those who have done so much work before.

ReplyDelete